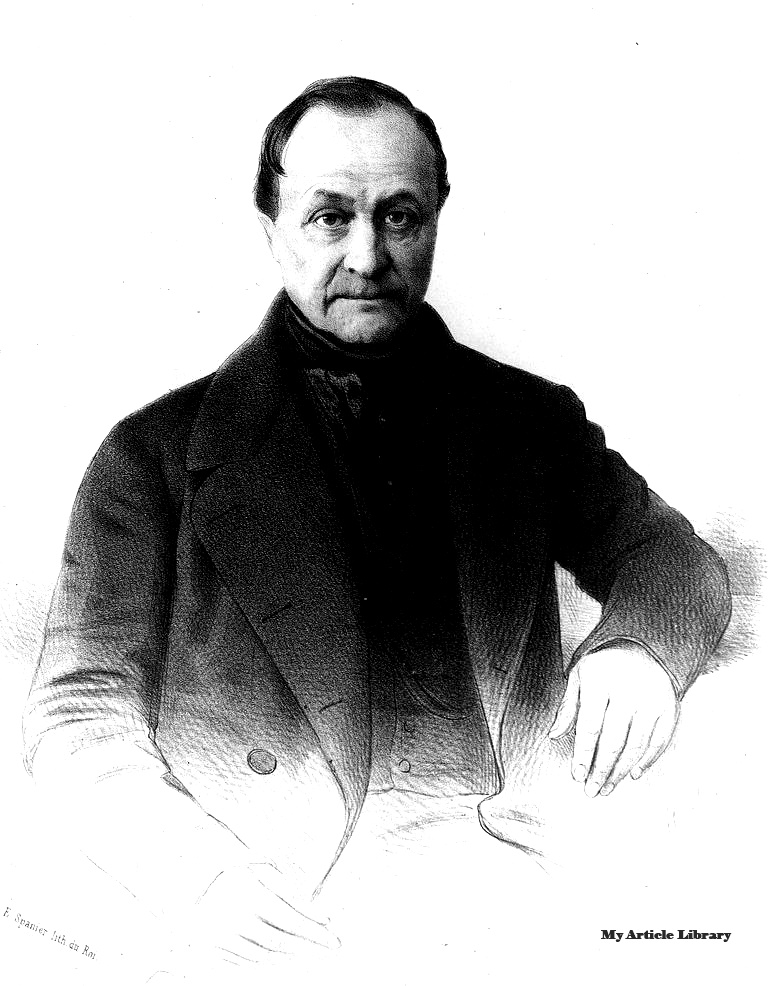

The Father of Sociology

August Comte

The French author Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748-1836) first used the term "sociology" in a manuscript that was never published in 1780 (Fauré et al. 1999). Auguste Comte coined the phrase in 1838. (1798–1857). In large part, the issues that motivated Comte to build sociology may be read into the inconsistencies of his life and the times he lived in. He was born in 1798, the sixth year of the young French Republic, to devout monarchists and Catholics who made a comfortable living off of the father's salary as a small-time bureaucrat in the tax office.

Comte originally studied to be an engineer, but after rejecting his parents’ conservative views and declaring himself a republican and free spirit at the age of 13, he got kicked out of school at 18 for leading a school riot, which ended his chances of getting a formal education and a position as an academic or government official.

He became a secretary of the utopian socialist philosopher Claude Henri de Rouvroy Comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825) until they had a falling out in 1824 (after St. Simon perhaps purloined some of Comte’s essays and signed his own name to them).

But they both believed that social science could be investigated using the same scientific techniques as the natural sciences. The motto "order and progress" was created by Comte to bring together the conflicting progressive and conservative factions that had split the crisis-ridden, post-revolutionary French society. Comte also believed in the ability of social scientists to contribute towards the improvement of society. The authority of science would be the mechanism by which members of each social stratum would be made to feel at peace with their place in Comte's envisioned new, organic spiritual order. His impact can be seen in the fact that the Brazilian coat of arms bears the phrase "order and progress." (Collins and Makowsky 1989).

Comte gave positivism as the term of the field of study for social patterns. A well-attended and well-liked series of lectures he gave outlining his philosophy were later published as The Course in Positive Philosophy (1830–1842) and A General View of Positivism. (1848). He felt that a new "positivist" era of history will begin as a result of employing scientific techniques to uncover the principles governing how society and individuals interact. The law of three stages, which he considered to be the cornerstone of his sociological theory, proposed that all human societies and all branches of human knowledge progress through three separate epochs, from the most primitive to the most sophisticated, namely the theological, the metaphysical, and the positive.The way a person perceives causality or considers their place in the universe was the essential variable in identifying these stages.

Humans explain causes in terms of the will of anthropocentric gods during the theological stage. (the gods cause things to happen). Humans explain causes in the metaphysical stage using speculative, abstract concepts like nature, natural rights, or "self-evident" truths. His criticism of the Enlightenment intellectuals, whose theories about inherent rights and liberties had inspired both the French Revolution and the anarchy that followed it, was based on this. He believed that the philosophers' "negative" or metaphysical knowledge was founded on dogmatic notions that were incommensurable when they were contracted. As a result, there was unresolvable strife and moral chaos.

Finally, human beings explain causes using scientific principles and rules in the positive stage (i.e., "positive" knowledge based on propositions restricted to what can be empirically observed). Comte thought that this would be the last stage of human social evolution since science would eliminate the causes of moral and intellectual anarchy, so bridging the gap between the political factions of order and progress. Positive philosophies would unite society and the sciences if they were applied. (Comte 1830).

Even if Comte's positivism is a little strange by modern standards, it started the positivist tradition in sociology's evolution. In theory, positivism is a sociological stance that seeks to investigate society using methods similar to those used by the natural sciences to study the world around us. In reality, Comte prefered the term "social physics" to describe this method because he considered it as the logical conclusion of the historical development of the sciences—the "sciences of observation" applied to social events. More specifically, positivism for Comte:

- “Regards all phenomena as subjected to invariable natural laws”

- Pursues “an accurate discovery of these laws, with a view of reducing them to the smallest possible number”

- Limits itself to analyzing the observable circumstances of phenomena and to connecting them by the “natural relations of succession and resemblance” instead of making metaphysical claims about their essential or divine nature (Comte 1830)

Although Comte didn't actually conduct any social research and used the laws that governed what he called the general human "mind" of a society—which is difficult to observe empirically—as the object of analysis, his idea of sociology as a positivist science that could successfully socially engineer a better society had a significant impact. His beliefs evolved from positivism as the "science of society" to positivism as the foundation of a new cult-like, technocratic "religion of humanity," which is where his influence began to decline. He also became more hostile to all criticism at this point.

He envisioned a new social structure that was extremely conservative, hierarchical, and akin to a caste system in which every level of society was required to accept its "scientifically" determined position. Comte gave himself the title of "Great Priest of Humanity," envisioning himself as the apex of civilization. He predicted that the reign of sociologists would end the moral and intellectual anarchy, but only by doing away with the need for pointless and disruptive democratic discourse. Social order "must always be incompatible with an ongoing debate about the fundamentals of society" (Comte 1830).

0 Comments